What is herpetic eye disease?

Herpetic eye disease or ocular herpes refers to any eye problem due to infection by the herpes simplex virus. There are 2 main types of herpes simplex virus: herpes simplex virus 1 (which causes mouth ulcers and herpetic eye disease), and herpes simplex virus 2 (which causes genital ulcers and rashes).

The herpes virus is very common and very contagious. After causing the initial infection, it remains quiescent within the nervous system of the host but it can reactivate and cause problems. It is estimated that one third of the population worldwide suffers from recurrent herpes infections. Herpetic eye disease is the most common cause of corneal blindness in the United States.

Please note that ocular herpes is NOT a sexually transmitted disease.

What happens when I get herpetic eye disease?

The herpes simplex virus, like the herpes zoster virus, can affect any part of the eye, from the front (eyelids) all the way to the back (retina). Generally, the further back the virus has infected, the worse the disease is.

Primary herpes infection: This is when the herpes simplex virus infects the patient for the first time, usually during childhood. The eyelids around the eye are affected, but the eyeball itself may not. The rash and vesicles (see left) can be uncomfortable, but tend to resolve by themselves after several weeks.

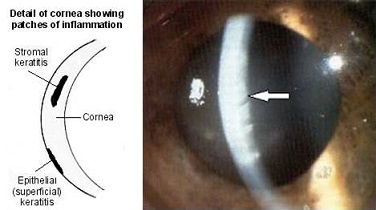

Dendritic ulcer / Epithelial keratitis: In this condition, the herpes virus replicates in the corneal epithelium (outermost layer of the cornea, which is the front ‘window’ of the eye) to form the typical dendritic ulcers (see right; white arrows). The eye will feel irritated and sensitive to light. If untreated, it can cause scarring of the cornea, resulting in reduced vision.

Neurotrophic ulcer: The herpes simplex virus can also affect the nerve to the cornea. This causes reduced corneal sensation and reduced tear formation. As a result, the cornea becomes very dry and the corneal epithelium degenerates (see left; white arrow), thus exposing the corneal tissue underneath to further infection and trauma.

Herpetic stromal keratitis: The herpes simplex virus can also cause inflammation in the corneal stroma (wall of the cornea; see below). This blurs the vision and is often accompanied by inflammation in the eye. The eye pressure may also become elevated, thus increasing the risk of glaucoma. In severe cases, the corneal tissue may become permanently scarred or be thinned to the point of perforation.

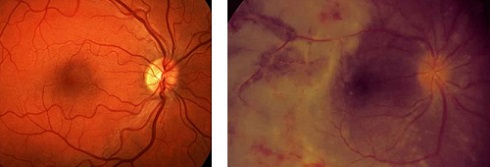

Acute retinal necrosis: The retina is the light-sensitive innermost lining of the eyeball, which detects, absorbs and processes the light that enters the eye. In severe herpetic eye disease, the retinal tissue can become inflamed and necrosed. This is uncommon, and tends to happen more in people who already have a depressed immune system, such as HIV patients or transplant patients who are on strong anti-rejection medications. This can progress to retinal detachment and the outcome is generally poor.

Left: Picture of a normal retina with a healthy optic disc and macula

Right: Acute retinal necrosis with severe retinal inflammation and optic disc swelling

How is herpetic eye disease diagnosed?

One of the hallmarks of herpetic eye disease is reduced corneal sensation. Your ophthalmologist will use the tip of some cotton wool (or tissue) to gently touch the front surface of the cornea. If your corneal sensation is intact, you will be able to feel the cotton wool easily. If your corneal sensation is absent, you will not be able to feel the cotton wool.

The definitive way to diagnose herpetic eye disease is by taking a sample from the eye for analysis with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). If the herpes simplex virus DNA is detected, then the diagnosis of herpes simplex infection is confirmed. The sample can be from the conjunctiva (conjunctival swab), the anterior chamber (aqueous tap), and the vitreous cavity (vitreous tap).

How is herpetic eye disease treated?

Mild ocular herpes tends to resolve spontaneously over several weeks without any treatment. However, if the cornea is affected, it is generally a good idea to start treatment to reduce the risk of corneal scarring.

Anti-viral treatment: This is the mainstay of therapy, and can be in the form of eye drops (trifluorouridine), eye ointment (aciclovir), or tablets (aciclovir, famciclovir, and valaciclovir). For dendritic ulceration, the anti-viral eye drops or ointment are instilled at least 5 times daily for a few days; this is then reduced or stopped according to clinical response. Oral anti-virals are used as a preventative measure for recurrent ocular herpes. In very severe disease, such as acute retinal necrosis, the anti-viral will need to be given directly into the bloodstream (intravenous administration).

Steroid eye drops: In general, steroid eye drops are not a good idea because they reduce the immune response of the eye to the infection. However, once the anti-virals get the infection under control, the steroid eye drops will help to settle any inflammation in the eye and promote recovery. Steroid eye drops are particularly useful when there is herpetic stromal keratitis or uveitis.

Lubrication: Eyes with previous or current active herpetic eye disease tend to have dryness of the ocular surface, which can slow down the healing process. Actively lubricating the eyes with preservative-free eye drops or gels or ointment (the lubricants are the same as those used for dry eye treatment), help with the recovery process. Preservative-free lubrication is vital in neurotrophic ulcers.

Corneal graft: Corneal transplant surgery is indicated when the herpes simplex infection has resulted in severe scarring of the cornea. This involves removing the unhealthy, scarred cornea and replacing it with normeal, healthy cornea from a donor. However, the risk of corneal transplant failure is high in such cases. Such patients often need to be on long term aciclovir tablets and steroid eye drops.